Quantitative easing in Europe: effect for Baltics’ economy

The European Central Bank announced recently a large program of quantitative easing (QE), involving a purchase of over ˆ1 trillion of assets (mainly government bonds) in the euro-zone countries. It’s a huge change from a conservative ECB’s position in monetary policy with possible strong effect for economy and business in the three Baltic States.

The ECB’s program of excessive liquidity is aimed at purchasing each month, starting from March 2015 until September 2016, of about ˆ 60 bln of governments’ bonds. This is at a time of almost zero interest rates, slow growth and inflation in the EU. Besides, some say, the euro-zone states’ deflation threat has become too serious as well. The Financial Times argues that „whether this is a case of better late than never or too little too late“; it remains to be seen.

Europe is the last in line…

Several central banks in the world have used monetary interference (the type of QE-programs’ approach) to tackle the 2008-crisis aftermath, e.g. first was the Federal Reserve in the US (and it made already three attempts to repeat QE), then the Bank of England, followed by the Bank of Japan, etc. The banking sector in Europe finally seems to be recovering, following another stress tests in 2014.

However, fiscal policy is not very supportive for growth, but it is not any longer becoming restrictive; neither the monetary policy…

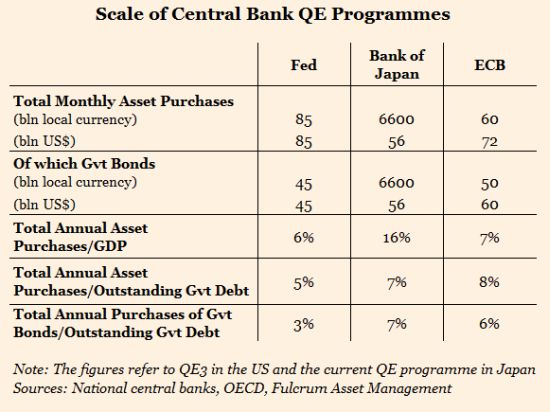

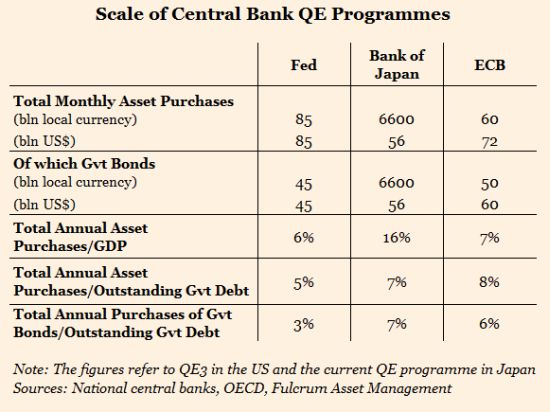

The markets are likely to assess the package with the next months; however good expectations might outweigh the negative. The table below gives a certain vision of such optimism

European QE-program would continue over September 2016, until the ECB governing council „sees a sustained adjustment in the path of inflation“ consistent with its inflation target, as ECB President has said. It goes hand-in-hand with the previous ECB’s commitment to increase the balance sheet back to the early 2012 level, and offers an expectation that there will be more if needed.

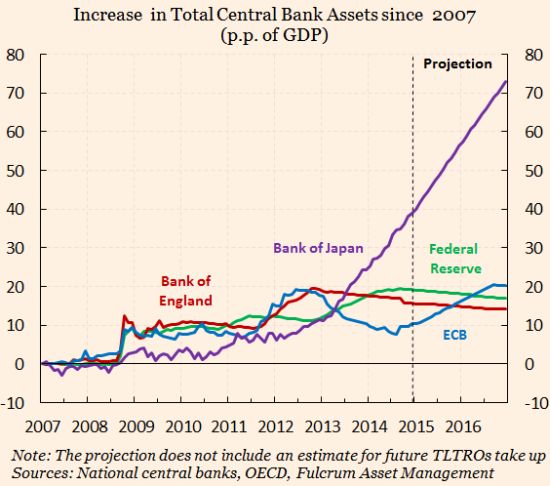

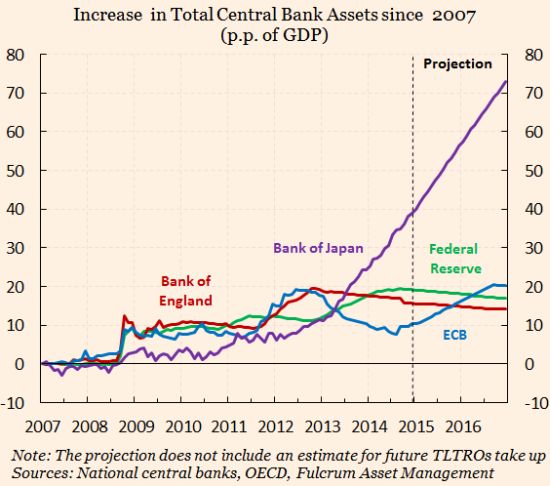

It is certainly difficult to measure now with accuracy the QE program; however comparing with other countries it is seen that the increase in central bank assets was at the level of 15-25 per cent with rising inflation (see table below).

QE’s pros & cons…

The outcome of QE’s program of the bond purchases is not certain; e.g. the Bundesbank (Germany is generally anticipated the idea) and others seem to have required that 80 per cent of the default risks should remain on the balance sheets of the national central banks, thus giving a signal that the EU monetary union is not quite stable either.

European economists have already hotly disputed whether the QE was necessary to prevent de facto fiscal risk-sharing via the ECB balance sheet and, if so, whether it undermines the monetary policy benefits of QE, argued the Financial Times.

Most economists seem to agree with ECB, that, in normal circumstances, the intended monetary easing is not compromised by the absence of full risk sharing. However, in a confidence crisis, this decision could add to speculation against the integrity of the single currency itself. That may be a price that the ECB thought was worth paying to bring „a large majority“ of his governing council onside with the decision taken, underlined the Financial Times.

As to the decision-making at the ECB, it behaved like any other central bank, where contentious decisions are routinely taken by a majority vote, sometimes a very small majority. But the Bundesbank has always been special, so this is a novel experiment for the ECB. What seems clear from recent events, writes the Financial Times, is that the Bundesbank no longer has a veto, which is what matters for the path and effectiveness of monetary policy. And, in a separate vote, the German central bank has now formally joined all the rest in unanimously agreeing that QE is a valid tool of monetary policy and important for the European future economic progress.

QE’s implementation needs structural reforms

Present QE’s proposal shall be seen in line with the Commission’s ˆ 315 bln investment fund’s idea published by the Commission in January 2015. Additional liquidity is regarded as an important stimulus for investment and activating internal consumption.

But, at the same time, the progressive structural reforms are needed too to streamline perspective financial resources. Here, as the ECB once said, „all measures are appropriate („whatever it takes“).

Only structural reforms in the member states can make the market more flexible and dynamic. As soon as such reforms are going to be expensive, the banks shall use the QE liquidity for supporting such reforms. It is going to be big challenge for the Baltic States’ parliaments to adopt needed structural reforms aimed at growth potentials with more productive and competitive structural policies. The Baltic economy, business and the market will support only such reforms…

The absence of structural reforms in labour and product markets has taken the underlying trend growth rate in the euro-zone to below 1 per cent, less than half in the US. Modern politicians have to recognise that structural reforms and monetary „accommodations“ could easily go hand-in-hand; in fact, they should reinforce one another, as the ECB’s move into QE emphasised.

Besides, the QE decision underlines the necessity for boosting growth through more flexible euro-zone’s budget rules. In mid-January, the Commission already announced the plan of relaxing EU’s budget rules.

Some critical opinions on QE

Expert opinion from the Financial Times goes that „the announced QE could decrease bank lending, not increase it. The explanation is the following: euro-area government debt is about ˆ 6.7 trillion, around 25% of that (ˆ 1.7 trln) is directly held by banks, the remainder by investors, about ˆ 5.0 trln.

Assuming that the ECB buys 30% of all euro-zone government bonds (ˆ 2.0 trn if they continue beyond ˆ 1.1 trn) in proportion to the current bank/investor ratio of 25%/75%, then the balance sheet of euro-zone -banks will expand by ˆ 1.5 trln in reserves. Besides, about ˆ 2.0 trn minus ˆ 0.5 trn of government bonds on the banks balance sheet are already converted into reserves.

The Financial Times makes to suggestions concerning the effect of bigger balance sheet in the banking sector:

1) The banking sector has to raise equity capital to comply with leverage ratios. If you assume a 5% minimum leverage ratio, then banks would have to raise an additional ˆ 75 bln in equity capital. The cost of equity capital is around 10% whereas they will not receive any interest on excess reserves, quite the opposite; QE could be regarded as „a tax on banks“.

Providing loans to corporations or consumers is also constrained as the banks have also to comply with liquidity provisions. Thus, after the member states’ banks have sold their liquidity to the ECB and given the liquidity constraints, the banks will rather decrease lending than to increase it.

2) Contrary to the intention of the ECB to increase lending, argue the Financial Times, QE could actually decrease lending.

Conclusion

QE doesn’t work in a lot of economic systems as it creates money supply and inflation problems at the same time: the main way to create inflation in the real economy is through bank-led credit creation, something that is difficult as banks are being regulated aggressively, restricting lending. The other way would be to give printed money directly to households. Printing money and hoping it dissipates throughout the system doesn’t work when the mechanics of the capitalist system are suppressed, through regulation and low bond yields, argue the Financial Times.

Quantitative easing (QE) is not to be seen as panacea for European economy, especially in the euro-zone, where bank borrowing dominates bond funding for private companies.

Nevertheless, genuine progress has been made. At the ECB, the monetary component of the EU bank has finally been delivered; politicians in the member states now have work to do on the fiscal and structural components.

The ECB’s program of excessive liquidity is aimed at purchasing each month, starting from March 2015 until September 2016, of about ˆ 60 bln of governments’ bonds. This is at a time of almost zero interest rates, slow growth and inflation in the EU. Besides, some say, the euro-zone states’ deflation threat has become too serious as well. The Financial Times argues that „whether this is a case of better late than never or too little too late“; it remains to be seen.

Europe is the last in line…

Several central banks in the world have used monetary interference (the type of QE-programs’ approach) to tackle the 2008-crisis aftermath, e.g. first was the Federal Reserve in the US (and it made already three attempts to repeat QE), then the Bank of England, followed by the Bank of Japan, etc. The banking sector in Europe finally seems to be recovering, following another stress tests in 2014.

However, fiscal policy is not very supportive for growth, but it is not any longer becoming restrictive; neither the monetary policy…

The markets are likely to assess the package with the next months; however good expectations might outweigh the negative. The table below gives a certain vision of such optimism

European QE-program would continue over September 2016, until the ECB governing council „sees a sustained adjustment in the path of inflation“ consistent with its inflation target, as ECB President has said. It goes hand-in-hand with the previous ECB’s commitment to increase the balance sheet back to the early 2012 level, and offers an expectation that there will be more if needed.

It is certainly difficult to measure now with accuracy the QE program; however comparing with other countries it is seen that the increase in central bank assets was at the level of 15-25 per cent with rising inflation (see table below).

QE’s pros & cons…

The outcome of QE’s program of the bond purchases is not certain; e.g. the Bundesbank (Germany is generally anticipated the idea) and others seem to have required that 80 per cent of the default risks should remain on the balance sheets of the national central banks, thus giving a signal that the EU monetary union is not quite stable either.

European economists have already hotly disputed whether the QE was necessary to prevent de facto fiscal risk-sharing via the ECB balance sheet and, if so, whether it undermines the monetary policy benefits of QE, argued the Financial Times.

Most economists seem to agree with ECB, that, in normal circumstances, the intended monetary easing is not compromised by the absence of full risk sharing. However, in a confidence crisis, this decision could add to speculation against the integrity of the single currency itself. That may be a price that the ECB thought was worth paying to bring „a large majority“ of his governing council onside with the decision taken, underlined the Financial Times.

As to the decision-making at the ECB, it behaved like any other central bank, where contentious decisions are routinely taken by a majority vote, sometimes a very small majority. But the Bundesbank has always been special, so this is a novel experiment for the ECB. What seems clear from recent events, writes the Financial Times, is that the Bundesbank no longer has a veto, which is what matters for the path and effectiveness of monetary policy. And, in a separate vote, the German central bank has now formally joined all the rest in unanimously agreeing that QE is a valid tool of monetary policy and important for the European future economic progress.

QE’s implementation needs structural reforms

Present QE’s proposal shall be seen in line with the Commission’s ˆ 315 bln investment fund’s idea published by the Commission in January 2015. Additional liquidity is regarded as an important stimulus for investment and activating internal consumption.

But, at the same time, the progressive structural reforms are needed too to streamline perspective financial resources. Here, as the ECB once said, „all measures are appropriate („whatever it takes“).

Only structural reforms in the member states can make the market more flexible and dynamic. As soon as such reforms are going to be expensive, the banks shall use the QE liquidity for supporting such reforms. It is going to be big challenge for the Baltic States’ parliaments to adopt needed structural reforms aimed at growth potentials with more productive and competitive structural policies. The Baltic economy, business and the market will support only such reforms…

The absence of structural reforms in labour and product markets has taken the underlying trend growth rate in the euro-zone to below 1 per cent, less than half in the US. Modern politicians have to recognise that structural reforms and monetary „accommodations“ could easily go hand-in-hand; in fact, they should reinforce one another, as the ECB’s move into QE emphasised.

Besides, the QE decision underlines the necessity for boosting growth through more flexible euro-zone’s budget rules. In mid-January, the Commission already announced the plan of relaxing EU’s budget rules.

Some critical opinions on QE

Expert opinion from the Financial Times goes that „the announced QE could decrease bank lending, not increase it. The explanation is the following: euro-area government debt is about ˆ 6.7 trillion, around 25% of that (ˆ 1.7 trln) is directly held by banks, the remainder by investors, about ˆ 5.0 trln.

Assuming that the ECB buys 30% of all euro-zone government bonds (ˆ 2.0 trn if they continue beyond ˆ 1.1 trn) in proportion to the current bank/investor ratio of 25%/75%, then the balance sheet of euro-zone -banks will expand by ˆ 1.5 trln in reserves. Besides, about ˆ 2.0 trn minus ˆ 0.5 trn of government bonds on the banks balance sheet are already converted into reserves.

The Financial Times makes to suggestions concerning the effect of bigger balance sheet in the banking sector:

1) The banking sector has to raise equity capital to comply with leverage ratios. If you assume a 5% minimum leverage ratio, then banks would have to raise an additional ˆ 75 bln in equity capital. The cost of equity capital is around 10% whereas they will not receive any interest on excess reserves, quite the opposite; QE could be regarded as „a tax on banks“.

Providing loans to corporations or consumers is also constrained as the banks have also to comply with liquidity provisions. Thus, after the member states’ banks have sold their liquidity to the ECB and given the liquidity constraints, the banks will rather decrease lending than to increase it.

2) Contrary to the intention of the ECB to increase lending, argue the Financial Times, QE could actually decrease lending.

Conclusion

QE doesn’t work in a lot of economic systems as it creates money supply and inflation problems at the same time: the main way to create inflation in the real economy is through bank-led credit creation, something that is difficult as banks are being regulated aggressively, restricting lending. The other way would be to give printed money directly to households. Printing money and hoping it dissipates throughout the system doesn’t work when the mechanics of the capitalist system are suppressed, through regulation and low bond yields, argue the Financial Times.

Quantitative easing (QE) is not to be seen as panacea for European economy, especially in the euro-zone, where bank borrowing dominates bond funding for private companies.

Nevertheless, genuine progress has been made. At the ECB, the monetary component of the EU bank has finally been delivered; politicians in the member states now have work to do on the fiscal and structural components.

Eugene Eteris baltic-course.com

Articles »

Quantitative easing in Europe: effect for Baltics’ economy »

Views: 21638 Diplomatic Club

Appeal to world leaders and humanity

Appeal to world leaders and humanity